OH, YOU THINK SO?

When my younger daughter moved out on her own, she left a copy of her music library on our kitchen computer. For years I hadn’t listened seriously to anything recorded later than the 80s, but I wanted to know what mattered to her and to other kids her age—especially to girls—so I started listening to her music. I found some great artists who were brand new to me—Cat Power, Postal Service, Iron and Wine, Metric, Sufjan Stevens, Tegan and Sara, Portishead. I also found hours of electronica, much of it unlabeled. I dimly sensed a change blowing in the cultural wind, so I wandered onto the net in search of something I knew I wouldn’t be able to identify until I’d found it. I wanted to experience a connection with what was going on right now as intensely as I’d felt when I first heard Bob Dylan in 1963.

The traditional music industry was collapsing—any kid with a computer could make a song and publish it—so what I was expecting to find was a lot of junk, but no; there was a massive amount of new, exciting, interesting music, so much that no single person could possibly keep track of it. I was fascinated by the minimal bands that consisted of no more than a girl, a boy, and a computer, and one of them finally gave me the experience I’d been looking for. The moment I heard the girl’s voice dropping into place on top of a hard electronic beat, I thought, yes, that’s it! She had exactly the tone of voice a border guard might use to say, “Could you step this way, please?” What she said was, “Oh, you think so? Well, I know so.”

The duo was “The Hundred in the Hands.” Their song, “Dressed in Dresden,” may be one of the bleakest love songs ever recorded. “You be bombed Berlin,” Eleanore Everdell sings, “and I’ll play Stalingrad.” Their lovemaking is reduced to “In and out, and out and in.” Where are they? “These are our times. The End Times.”

The duo was “The Hundred in the Hands.” Their song, “Dressed in Dresden,” may be one of the bleakest love songs ever recorded. “You be bombed Berlin,” Eleanore Everdell sings, “and I’ll play Stalingrad.” Their lovemaking is reduced to “In and out, and out and in.” Where are they? “These are our times. The End Times.”

OBLIVION

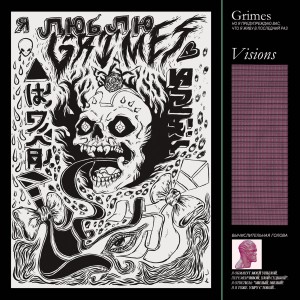

I still didn’t know where I was going, but I was going—following clue to clue. Those minimal bands consisting of a girl, a boy, and a computer could get even more minimal—they could dispense with the boy. In her early interviews, Claire Boucher comes across as a young artist utterly devoid of pretensions. At the end of her conversation with Nardwuar, the zany guerilla interviewer, he asks her, “Why should people care about Grimes?” She doesn’t have to think about it, answers quickly, “Because it’s the future,” then hesitates for a micro-beat and adds, “of music.”

I drove around for weeks with the complex layers of Grimes’ Visions on my car stereo. Claire has a girl’s voice—light, clear, and perfectly pitched. As Grimes, she uses it as an instrument, folding it into the mix. The songs do have lyrics, but they’re hard to hear, and it took me a long time to become aware of them. Sharper ears than mine have decoded the opening of “Oblivion,” but when I read the words, I listened again, and, yes, that really is what she’s singing:

I never walk about after dark.

It’s my point of view.

‘Cause someone could break your neck

coming up behind you,

always coming and you’d never have a clue.

The video for “Oblivion” opens with a shot of Grimes in a men’s locker room. She’s wearing black tights and a long baggy sweatshirt that effectively hides her figure. A circle of diaphanous gauze protrudes from the bottom of the sweatshirt like a whimsical reference to a petticoat. She’s flanked by two buff young men wearing nothing but towels. We follow her into a stadium to watch motorcycles leaping off jumps and sailing through the air. Cut to another stadium and we’re at a football game, complete with a squad of conventionally cute cheerleaders. Enter some semi-naked young men acting like drunken jerks. Shots place Grimes at the center of various of these male-centric preserves. As the music gets darker, the semi-naked jerks begin to mock fight with each other. As a concluding chorus, Grimes sings, “See you on a dark night.” The last we see of her—in a dress with a huge girly white collar—she has just popped her bubblegum.

In Musicfeeds Claire tells Jacinta Govind that “Oblivion” is “about being violently assaulted,” says that it made her crazy for years. “I got really paranoid walking around at night and started feeling really unsafe. The song is more about empowering myself physically amongst a masculine power, and the hate of feeling powerless, making light of masculine physical power, making it jovial and non-threatening. I took a typically violent cultural situation and made it pop and happy.”

I tried to remember if the video had looked “pop and happy” to me when I’d first seen it—and it probably had—but knowing Claire’s story cast a shadow over it, and I could never see it quite that way again.

This spring (April, 2013) Grimes posted a powerful statement on her Tumblr blog: “I don’t want to have to compromise my morals in order to make a living.” Within a couple of days the net—that infinite hall of mirrors—reproduced it endlessly. I started counting the sites that had reposted it, either in whole or in part, but I stopped when I hit thirty, nowhere near the end. The comments from the bloggers were almost always positive. The standard headline said something like, “Grimes criticises sexism in the music industry.”

Most of her complaints are about men who try to hit on her or her dancers—or condescend to her, offering to “help her out” as though, as a woman, she doesn’t know what she’s doing—or don’t take her seriously when she’s concerned about her physical safety. “I don’t want to be infantilized because I refuse to be sexualized,” she says, and “im tired of being referred to as ‘cute,’ and a ‘waif’” She finds it “sad that it’s uncool or offensive to talk about environmental or human rights issues.”

“I’m sad that my desire to be treated as an equal and as a human being is interpreted as hatred of men” she writes, “rather than a request to be included and respected (I have four brothers and many male best friends and a dad and i promise i do not hate men at all, nor do i believe that all men are sexist or that all men behave in the ways described above)”

SHUT UP AND CARRY ON

Metric’s Emily Haines is a few years farther than Grimes down the rocky road of the music industry. She tells The Guardian’s Rebecca Nicholson that the distinction between men and women in rock is “unnecessary” and creates “a pink ghetto”— “This has been pissing me off for a long time, but then you don’t want to be an angry woman. You’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t.”

The occasion of the interview is the release of Synthetica, Metric’s fifth album, an ambitious and complex work that has a lot to say—not only about a dystopian future but about a dystopian present. “Culture has completely fucked over the next generation,” Haines says. “Hey, guess what? You can look forward to horrible pollution and climate change and hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt. No jobs. Thanks guys. Cheers for the plan.”

Haines invokes a time when “thousands of people gathered around listening to Bob Dylan songs, Hendrix playing All Along the Watchtower, that level of communication happening on a mass cultural scale. I was feeling like, ‘Ah, man, I haven’t done that.’ ” She may not have done that, but she’s definitely struck the heart of at least one listener. No album since the 60s has hit me as hard as hers. For me, Synthetica is to 2012 as Highway 61 Revisited was to 1965.

Haines invokes a time when “thousands of people gathered around listening to Bob Dylan songs, Hendrix playing All Along the Watchtower, that level of communication happening on a mass cultural scale. I was feeling like, ‘Ah, man, I haven’t done that.’ ” She may not have done that, but she’s definitely struck the heart of at least one listener. No album since the 60s has hit me as hard as hers. For me, Synthetica is to 2012 as Highway 61 Revisited was to 1965.

“Dreams So Real” is at the dark heart of the album. The narrator mourns for a time when, “Our parents, daughters and sons believed in the power of songs. What if those days are gone?” Hearing that, I took it personally. I am one of those parents—it’s my generation who believed in the power of songs. Back in the day we asked each other, “What are you listening to?” and it was a serious question. Music was the glue that held us together. Dylan or Country Joe or the Airplane or the Doors or the Dead were not for entertainment; they were for direction, confirmation, revelation.

“My memory is strong,” Haines sings, and then she’s riffing off Dylan’s “not busy being born is busy dying,” but times have changed since then, become far worse. “Anyone not dying is dead,” she tells us, “and maybe it won’t be long.” When people call kids today “apathetic,” they’re using the wrong word. It’s not “apathy,” it’s stifled despair, and Haines has nailed it:

So shut up and carry on.

The scream becomes a yawn.

You can shut up and carry on, but you can’t stop the reality nightmares:

All of the unknown, dying or dead,

keep showing up in my dreams.

They stand at the end of my bed.

Have I ever really helped anyone but myself

to believe in the power of songs?

to believe in the power of girls?

With “the power of girls,” Haines is invoking those girls who had been on the road just a little bit ahead of her—not the Spice Girls with their sweetened, trivialized version—but the original Riot Grrrls. Even after all these years, Kathleen Hanna’s words can still ring just as fierce and true as when she wrote them:

BECAUSE I believe with my wholeheartmindbody that girls constitute a revolutionary soul force that can, and will change the world for real.

©Keith Maillard, 2013

This is an exciting and thought provoking article. It’s helping me to feel the momentum of women in the world right now. It’s an exciting time. And you offer a a powerful insight.